When the Tech Revolution Came to Wall Street

Marty Fridson began his financial career in 1976. He experienced the explosion of technological tools available to securities analysts.

We take for granted nowadays the technology that’s essential to doing our jobs in the securities market. Yet when I started out as a corporate bond trader in 1976, there were no cellphones—much less smartphones—no personal computers, no electronic spreadsheets, no email, and no Internet. No Google, no FRED, no PowerPoint. I kept track of my bond inventory with a ballpoint pen and 4” x 6” index cards, one card for each bond I traded. My group had no real-time electronic hookup to the government bond market, so we didn’t think in terms of spread-versus-Treasuries. Instead, we formulated our bids and offers based on trades in benchmark corporate issues, which interdealer brokers phoned to us.

To store telephone numbers and record my appointments, I carried a shirt-pocket-sized, black-vinyl-bound address book everywhere I went. When the new calendar-year’s edition became available, I laboriously copied all my addresses into it. This system exposed me to some ribbing because the phrase “little black book” was associated with Lotharios who maintained inordinately long lists of lady friends. (Of course, today I carry a 3” x 6” hunk of metal and glass everywhere I go. I’m not certain that is a 100% net improvement.)

Because I was working at a firm with no credit research department—analysts had only recently began migrating from the rating agencies to the sell side—the fundamental information on the bonds I traded came mostly from print publications such as Moody’s Bond Record and Standard & Poor’s Bond Guide. I sometimes learned that a rating change had occurred in-between issues of those monthlies only by reading about it in the newspaper the next day.

This led to my getting picked off on some Consolidated Edison bonds that I failed to mark up before trading started the morning following their upgrade to investment grade. I’d read the New York Times on my short subway ride into the office instead of the Wall Street Journal. My boss contended that the Times had the better market coverage, so I usually scoured the Journal at a later hour. For some reason, the Times didn’t report the Con Ed upgrade that day. So when I got to my desk before anyone else had arrived, the phone rang earlier than it ever had before. A trader from another firm had seen the Con Ed bonds I offered in the Blue List, a daily collection of municipal and corporate offerings, at a cheaper price than they were certain to be quoted at once trading got started. When I confirmed that my offer was still good, he quickly replied, “I buy!”

Kudos to that trader for his heads-up play, but I don’t think that kind of information lag could occur nowadays. And to be fair to myself, this was a freak event. I wouldn’t have kept my job if I wasn’t ordinarily on top of my markets. Grinding away in the era’s low-tech mode, I produced a steady trading profit by buying low and selling high, without putting the firm’s capital at great risk. I’m just glad other rookie traders have since been spared similar embarrassment, thanks to advances in information technology.

When I later moved into research, I wrote my reports by longhand. Only secretaries were equipped with word processors—big, clunky pieces of equipment with a function that hadn’t yet been incorporated into personal computers. Retrieving a past news story meant taking the elevator to the company library and leafing through physical back copies of the Wall Street Journal. If I was scheduled to make a presentation, I had to confirm that the venue had a slide projector for me to load my slides into.

A major part of my credit analysis consisted of obtaining printed 10-Ks and 10-Qs from the library and calculating a series of financial ratios with the help of a four-function calculator. I would then compare those ratios to averages for rating categories and industries that the research department’s statistical chief provided in looseleaf notebooks. I also spent a good deal of time clipping articles from Businessweek and other periodicals and filing them in folders that I maintained on each company I followed.

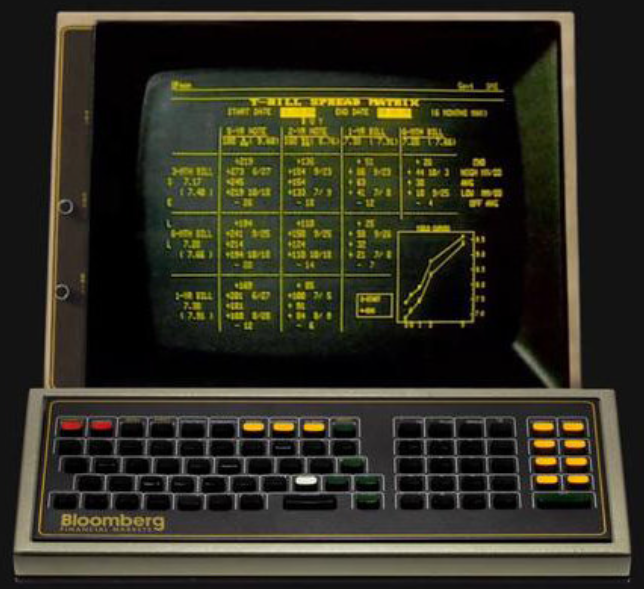

Technology began to improve on these primitive methods in the 1980s. VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet program, was introduced just before the decade began. The rise of the PC democratized computer power that was previously concentrated in the hands of those with access to mainframes. Bloomberg terminals first became available in 1982.

As powerful as these inventions were, they didn’t remake the investment business overnight. Transformation doesn’t come about through technological innovation alone. People’s habits also must change. So the transition to the new order had a behavioral as well as a digital component.

For me, the definitive sign that a revolution had taken place arrived after I advanced from credit analyst to research director/strategist, still on the sell side. One day a junior analyst from an institutional customer called me. “I reproduced your model and it is correct,” he informed me. “Whew!” I thought. But I realized right then that the curtain had come down on the old-style investment strategist, who was an acknowledged expert by virtue of being an acknowledged expert. Just mastering the skill of speaking in an authoritative manner that defied contradiction would no longer suffice. With data now much more widely available than in the past, the gurus’ pronouncements would henceforth have to stand up to rigorous empirical scrutiny.

As analysts converted from graph paper to electronic spreadsheets, Fidelity began requiring sell-side credit analysts not just to publish projected financial ratios on their companies, but also to submit the spreadsheets that showed how they got to those conclusions. I was surprised that other buy-side shops didn’t immediately follow suit. Demanding to see the underlying work was a good way to smoke out a sell-side analyst who was simply putting out the numbers that the traders or investment bankers wanted portfolio managers to see.

The vastly increased efficiency of generating financial projections did have a downside. As competition among leveraged buyout sponsors heated up, the EBITDA multiples paid in the deals soared. Debt loads increased to levels that made it unlikely that the acquired businesses could generate enough cash to meet required interest and principal payments. But now the junior investment bankers tasked with putting together deal books could continue tweaking their assumptions and run scenario after scenario until they came up with one that appeared to work. The resulting “hockey stick” projections, so called for the improbably sudden rise in revenues and cashflows that they predicted, helped investment bankers sell bond underwritings that couldn’t have been “proven” viable by grinding out each possible financial scenario the old-fashioned way.

Yet another way that the technology revolution affected financial professionals’ work was the new kinds of companies that analysts followed. Established analytical methods worked well enough for Wall Street’s purposes on traditional industrials—automakers, capital goods producers, chemical companies, and so forth. Simply project earnings per share, assign a multiple, and voila! you have a price target. Leaving aside the fact that the great financial theorist Joel Stern had shown back in 1974 that EPS is irrelevant to stock valuation, things had gone along smoothly year after year in the Equity Research Department. But now there were these New Economy companies, built on the Internet, satellite-based broadcasting, biotechnology, and various other new technologies. They didn’t produce any earnings, according to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), yet the market assigned multi-billion-dollar market caps to them.

The classic example was an online bookseller called Amazon. From its 1997 IPO through the end of 1999, its quarterly GAAP net income steadily declined from minus $6.7 million to minus $323.2 million. Over that same period, Amazon’s market cap soared from $0.4 billion to $26.3 billion.

The natural reaction of many pundits was to dismiss Amazon as a demonstration of the madness of crowds. There were indeed dubious Internet-based companies that ultimately went bust, but Amazon wasn’t one of them. It evolved into a broad-based retailer with an immensely valuable web services business. Its market cap now is around $1 trillion.

What Amazon’s early detractors didn’t grasp was that GAAP was well-designed for nineteenth-century manufacturers, but not for New Economy companies. Amazon genuinely created economic value and generated free cash flow, the key indicator of that value, according to Joel Stern’s classic 1974 Financial Analysts Journal article, “Earnings per Share Don’t Count.” But many of the new breed of industrials reported negative earnings because under GAAP, they had to expense items such as R&D and customer acquisition costs. Those expenditures created enduring value—the definition of an asset—but because they weren’t stuff, like buildings or machines, GAAP didn’t allow them to be capitalized and then depreciated over multi-year periods. It took time for market veterans to get used to the new, tech-driven reality of value creation.

I can’t claim that I was at the forefront of every technological advance. No false modesty there; I can point to several analytical techniques that I pioneered. They include the distress ratio, econometric modeling of the high yield spread-versus-Treasuries (working with Jón Jónsson and Chris Garman), and the Equalized Ratings Mix approach to sector valuation. But when it came to utilizing new technology, I wasn’t a lover of gadgets for their own sake. To build up enthusiasm for a new idea, I needed to see how it would enable my team to provide increased value to investors.

One trend that I did get in early on was email distribution of research. I heard that investors were beginning to receive reports that way, so I asked one of our analysts, Kathryn Okashima, to investigate the feasibility. We were advised to hold off because the practice was soon going to be introduced more widely in the research department. I told Kathryn to keep at it. That turned out to be the right decision because, as I expected, it took the rest of the outfit another year to gear up. Our smaller group managed to launch email delivery very quickly, eliciting a highly positive response from customers.

The only problem was that once we had signed up 90 institutional customers for electronic delivery, our system’s capacity for sending emails was exhausted. So in the end we had to wait for some additional engineering to email our entire institutional customer list.

Once we got to that point, though, the technology worked quite well. And that enabled us to achieve something our team could be very proud of. The infamous attack on the World Trade Center occurred on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. Merrill Lynch had to vacate the nearby World Financial Center, scattering the content creators, production people, and support staff to makeshift home offices. Contact was soon reestablished through calls to people’s home landline phones. But I wondered if it was even conceivable that we could put out next week’s edition of our research publication, This Week in High Yield.

Nowadays, remote work is nothing out of the ordinary, but in 2001 physical separation imposed significant constraints on the publishing process. The report we ultimately managed to send out approximately on schedule didn’t look exactly like our normal publication and we weren’t able to include all our regular data features. But our weekly did reach customers. Getting it out was our personal act of defiance against the terrorists.

Another way in which technological advances have changed finance—for better or for worse, depending on your point of view—is by making markets more efficient. This provides a social benefit in the form of improved allocation of capital, but from the investor’s perspective, it means that it’s gotten harder to outperform the index. On the equity side, this has occurred partly through sophisticated methods such as high-frequency trading, in which computers are programmed to act on new information far more swiftly than a human can.

Another way that technology has made it harder to gain an edge is by enhancing law enforcement’s ability to spot suspicious trading patterns amid millions of transactions. Insider trading has been illegal for many decades, but the chances of getting caught were much lower back in the day when detecting it was akin to finding a needle in a haystack. Of course, regulation has also had a hand in making it more difficult for investors to profit from non-public information. Swiss banks relented somewhat on the secrecy that shady operators and kleptomaniacal dictators relied upon. Regulation FD, requiring corporations to disclose information simultaneously to all investors, removed much of the advantage formerly enjoyed by traders who were able to ingratiate themselves with corporate managements.

But one technological advance begets another. Deprived of the chance to make money the old-fashioned way, money managers devised new ways to get a leg up. Analysts began to scrape information from social media sites to gauge investor sentiment on securities. Researchers used satellite images and later deployed drones for tasks such as counting cars in mall parking lots to get a handle on retail activity. Another technique involved analyzing the language in corporate earnings calls to ascertain CEOs’ true feelings about their companies’ business prospects. Machine learning was employed to manage order routing and block trade allocation, as well as to obtain the best pricing.

There are risks in relying too heavily on artificial intelligence in these kinds of activities. For instance, the computer might encounter some sort of one-off development not covered in the model training, such as a natural disaster or a geopolitical shock. Then, in Sorcerer’s Apprentice-like fashion, the computer could start making bad predictions and initiating terrible trades.

Research departments must avoid another pitfall. Team members who collect and process data may lose sight of the analytical objective or never get acquainted with it in the first place. When a model spits out an unexpected or highly counterintuitive result, it’s essential to investigate. The surprising output may either provide a valuable new insight or reveal a previously undetected flaw in the model. But if the people responsible for updating the model don’t recognize that the result looks anomalous, some essential information may never come to the attention of the ultimate investment decision maker. So research organizations have to emphasize integration of various functions in the face of specialization by function. They need to make sure the people responsible for model upkeep understand the big picture.

This requirement can be seen either as a burden or as a reason to be encouraged. It suggests that despite miraculous technological advances few of us envisioned in the 1970s, robots can’t completely replace us, at least not yet. But to stay in the game, we all must continue to keep abreast of technology.

Martin Fridson is the Chief Investment Officer of Lehmann Livian Fridson Advisors, an SEC registered investment adviser managing investment portfolios for US investors. He also publishes the Forbes/Fridson Income Securities Investor newsletter. Green Magazine called Marty’s Financial Statement Analysis “one of the most useful investment books ever” while The Boston Globe said Unwarranted Intrusions: The Case Against Government Intervention in the Marketplace, should be short-listed for best business book of the decade. Investment Dealers’ Digest called Marty “perhaps the most well-known figure in the high yield world.”

To comment on a story or offer a story of your own, email Doug.Lucas@Stories.Finance

Copyright © 2022 Martin Fridson. All rights reserved. Used here by permission. Short excerpts may be republished if Stories.Finance is credited or linked.