Peasant Logic and the Russian GKO Trade

Joe Pimbley has a PhD in theoretical physics, but in this story, he talks about a type of common sense called “peasant logic.”

In 1997, I joined Sumitomo Bank Capital Markets’ New York office to create a credit derivatives business. That’s where and when I first heard about “the Russian GKO trade.” The guys at Sumitomo had put this trade on before I arrived. It had made money, but they had only been allowed to do the trade only once because the Tokyo head office made them stop. My new colleagues at Sumitomo were eager to get my opinion on the trade. Maybe they thought I had some sway with the folks in Tokyo and could get them permission to do the trade again. But I think they really just wanted someone to agree with their assessment of the trade’s risk and commiserate with them over their misfortune in not being able to repeat a profitable opportunity.

Russian Gosudarstvennye Kratkosrochnye Obyazatelstva (GKOs) were short-term zero-coupon ruble-denominated debt issued by the Russian government; the 1990s Russian version of US Treasury bills. What made them interesting to Sumitomo’s traders, and to a lot of other traders in 1997, was that they had a very high yield, sometimes 40%. The trade package that Sumitomo put together to take advantage of the GKO’s yield had three parts.

The first part, of course, was buying the GKO. But since Sumitomo wanted neither rubles nor ruble currency risk, the second part of the trade was a currency forward. On the maturity date of the GKO, Sumitomo promised to pay a counterparty the rubles it expected to receive from the Russian government. On that same date, Sumitomo’s counterparty promised to pay Sumitomo a specified number of US dollars.

Now, because Russian government interest rates are higher than US government interest rates, traders expect the ruble to decline in value against the dollar. So, the ruble-dollar exchange rate agreed to in the forward contract will eat up some of the 40% interest on the GKO. But even so, the agreed exchange rate in the future allowed an excellent return on the trade, around 30%.

- - - - -

Joe explains the interaction of interest rates and cross-currency exchange rates and why the 40% return in rubles was reduced to a lower return in US dollars.

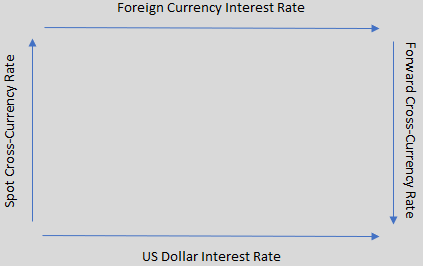

Finance professors illustrate the relationship between domestic interest rates, foreign-currency interest rates, and cross-currency exchange rates with the diagram below. The path of the line labeled “US Dollar Interest Rate,” from lower left to lower right, illustrates an investor buying a one-year US government security and holding it to maturity. He receives his principal back with interest in a year. This is the straight-forward way to invest today to receive US dollars in the future.

Alternatively, the investor could take a circuitous route around the rectangle. He would first change his US dollars into a foreign currency, as illustrated by the line going from lower left to upper left of the diagram labeled “spot cross-currency rate.” Now, having foreign currency, he would buy a one-year debt of a foreign government, denominated in that country’s currency, and hold it to maturity. That’s illustrated by the line going from upper left to upper right labeled “foreign currency interest rate.” Finally, because the investor does not want to assume the risk of what the exchange rate might be in one year, he would enter into a forward agreement to exchange foreign currency for US dollars in one year’s time at an exchange rate agreed to today. That is illustrated by the line going from upper right to lower right of the diagram labeled “forward cross-currency rate.”

To make their point about the relationship between interest rates and forward exchange rates clear, finance professors ask their students to temporarily assume away credit risk. Pretend there is no chance either government or the currency forward counterparty will default. With this assumption, an investor should be indifferent to which way he goes around the diagram, buying US dollar-denominated debt or converting US dollars into a foreign currency, buying foreign currency-denominated debt, and then later converting the foreign currency back into US dollars.

Appealing to the no-arbitrage or no-free-lunch rule, an investor shouldn’t make more money going one way around the diagram than the other way around the diagram. If foreign currency interest rates are higher, the forward exchange rate must cause the foreign currency to depreciate against the dollar. If dollar interest rates are higher, the forward exchange rate must cause the dollar to depreciate against the foreign currency. Or more precisely, if there is an advantage in one route, investors will rush into that route and their buying and selling will change prices until the two routes are back to offering the same return. Equilibrium will prevail and the difference between foreign currency and US dollar interest rates will be offset by the difference in spot and forward exchange rates.

- - - - -

Now everyone recognized that Russian government debt was not as safe an investment as US government debt. The Sumitomo traders were hoping to receive a 30% US-dollar return after buying the GKO and entering into the currency forward. But was 30% a fair return for taking the risk that Russia might default on the GKO? The Sumitomo traders were not sovereign credit analysts and they did not want to take Russian government default risk.

So, the guys at Sumitomo added a third leg to their trade package: they shorted Russian government debt. Now, your first reaction might be “if they are long Russian government debt and short Russian government debt, doesn’t that net to zero?” And it would, except Sumitomo shorted a Russian government bond denominated in US dollars.

The dollar-denominated Russian bond yielded far less than the currency-swapped GKO bond, about 10%. So, you had a 30% yield on the GKO swapped to dollars and the expense of shorting the Russian dollar-denominated bond yielding 10%. Sumitomo traders argued the trade made 20% after hedging out all currency and default risk.

The guys at Sumitomo also thought that the US dollar-denominated debt was a great hedge against Russia defaulting on its GKO. In fact, that was a big reason they liked the trade. They figured that Russia would be more apt to default on US dollar debt than the ruble-denominated GKO. The US dollar might appreciate more than expected against the ruble and make the dollar-denominated debt harder for Russia to pay. Or Russia might not have enough US dollar reserves to pay the dollar debt. Russia might implement foreign currency exchange controls.

The Sumitomo traders also figured Russia would be less likely to default on GKOs because these securities were mainly held by Russian citizens. The dollar-denominated debt was mostly held by institutions outside Russia. Wouldn’t Russia rather default to foreign institutions than to its own citizens? Besides, couldn’t the Russian government just print rubles to pay off the GKOs? The guys thought there was a real chance the GKO might pay in full while winnings from shorting defaulting Russian dollar debt would be pure profit.

So that was the trade my new colleagues were trying to convince me of, and I don’t mean that in any negative way, but they obviously wanted my buy-in that it was a great trade. “All the risk was taken care of and we were going to get a great return, but we weren’t allowed to do it,” they complained. Adding to the traders’ complaint was that who it was that said “no” was unclear. Sumitomo didn’t have an identifiable risk management department. Somebody far away, based in Tokyo, said “no” and traders in New York didn’t know who or why. My new colleagues clearly didn’t want me to analyze their trade and pick it apart; they were just looking for sympathy. So, I said “Yeah, that’s a really interesting trade.”

But less than a year later, in August 1998, GKO prices collapsed and yields spiked to 140%-170%. Then GKOs defaulted. The ruble went from six-to-the-dollar to 21-to-the-dollar. Russian inflation hit 85% and the entire top tier of Russia’s largest private banks failed.

Now, as I said, Sumitomo didn’t have the trade on. But when this all happened in Russia, I asked my colleagues about it. I’m thinking of one guy in particular, a managing director who really loved this trade and who wanted me to love the trade, too. I asked him, “What would have happened to your trade?” And his answer surprised me, because his answer was not, “It would have worked” or “It would have lost money.” His answer was “I don’t know.”

After a little more probing from me, I could see he had zero interest in my question. No curiosity whatsoever. Neither did any of the other Sumitomo traders involved in the GKO trade. I never heard anyone from Tokyo ask about the trade, either. And that struck me, that there was no curiosity at all on anyone’s part. For me, and I think for most people, life is a learning opportunity. If you have the opportunity to see what happened to somebody else and learn from it, you should take that opportunity. So, that’s part one of the story. And if there’s a moral to that part of the story, it’s “be curious.” But there are two more parts to the story, the “peasant logic” parts of the story.

Later in 1998, after Russia blew up, I attended a public risk management conference in Paris. And one of the speakers was Allen Wheat, CEO of Credit Suisse at the time. I didn’t know Wheat, but he impressed me as a blunt, direct-speaking guy. He talked about Credit Suisse’s version of the GKO trade. He didn’t mention a short position in a Russian-issued dollar bond, so maybe Credit Suisse didn’t bother with the credit risk hedge. But he talked about the GKO and rubles and the cross-currency forwards Credit Suisse executed with Russian banks. I didn’t mention it before, but the most active, willing counterparties to execute ruble cross-currency forwards were Russian banks.

He didn’t talk about the details of the trade; his message was higher level. And his higher-level message was that Credit Suisse had lost money on the trades and when he sought to find out why, he found finger pointing. The senior market risk guy said, “The trade was great from my perspective, we didn’t lose money because of market risk. The problem was the credit risk of the Russian banks. They didn’t honor their obligations on the forward currency transactions.” The senior credit risk guy told the opposite story. “We didn’t lose money because of counterparty credit risk. The problem was market movement.”

Interesting to me, Wheat’s story was not that he got to the bottom of this controversy and figured out what part of the loss owed to market risk and what part owed to credit risk. Wheat’s conclusion to his board of directors was that Credit Suisse had a problem with its “risk management philosophy.” It had market risk and credit risk silos when really risk management must be integrated. It’s unproductivee to distinguish market risk from credit risk if things are going to fall between the cracks and nobody’s going to take responsibility for understanding the complete risk picture.

Clearly, that’s a nice message, even if you wonder why Wheat didn’t work through the finger-pointing and hold people to account. Who can argue against an integrated approach to risk? But Wheat admitted he got chastised by his board when he presented that conclusion. The board said, “Allen, we think we understand what’s wrong here. It’s good to do all your analysis and get deep into the details, but at some point, you’re not seeing the big picture. You really need to use ‘peasant logic.’”

Wheat explained that “peasant logic” was the board’s term for what we might call “common sense,” but I like peasant logic better. The board said, “You people worry about how good your models are and you wonder about using two years of historical data or five years of historical data, and whether one is better than the other, and how much data you should have. We think you should have looked at the big picture and said, ‘messing around with 40% yields means there’s a lot of risk here. This is an unstable government and currency situation.’ We think you aren’t seeing the forest for the trees.”

So this was Wheat’s point: sometimes it’s good to forget the data and models and use peasant logic. In this case, if there are abnormal returns, there must be some abnormal risk. And I would say everyone in the audience, including myself, appreciated the point Wheat was making. I thought, “Here’s a global bank CEO being open about what they did wrong and how they need to do better, and he’s big enough to admit his bank’s mistakes.” All of that sounded great.

Then it came time for questions, and from the back of the room, someone had to shout out his question to be heard. And as soon as he started speaking, you could tell it’s a Russian accent and the guy is Russian. Being Russian lent authenticity to his remark, “You want historical data. I’ll give you 75 years of historical data. Russia has never honored any debt obligation.”

An exaggeration to be sure, but he didn’t say this in a rude or impolite way, although having to shout it from the back of the room it might have seemed that way. Maybe it did to Wheat, because unfortunately, Wheat’s reaction was to be annoyed. Wheat didn’t say, “Wow, what a great way to look at this. Why are we trusting Russian debt?” And he also didn’t say, “That’s a great example of the peasant logic the board was trying to impress upon me.”

The Russian continued. “I work for Merrill Lynch and we did this trade also and lost a lot of money. Beforehand, I told them it was a terrible trade because of Russia’s history and they didn’t listen to me because I’m just a mathematician.” Wheat still hadn’t cottoned to the idea that the Russian was helping him make his point about peasant logic, so he said in a rather dismissive, sarcastic way, “Well, I wish we had you working for us, then we wouldn’t have lost money. Right?”

Now it’s easy in hindsight, when you know how something worked out, to say “Aha, I knew such and such.” But still, I thought the Russian added to Wheat’s remarks and his remarks really made Wheat’s point. This guy in the audience was demonstrating peasant logic. The traders put all these fancy complex pieces together and think they’re really smart, but what the heck are they doing lending money to a government that, to this guy who is closer to it than the rest of us, you shouldn’t trust? So that’s part two of the story.

And then the third part of the story takes place a few years later in the 2000-aughts. My workplace at the time would have internal get-togethers to share good finance stories and what we learned from them. I told the GKO story, just as I’ve told it here. And one of my friends in the company spoke up. He’s Ukrainian, and he said, “Joe, great story. But the part of the story that I find most surprising is where the Sumitomo guys thought Russia was less likely to default on the ruble-denominated debt because it was predominately owned by Russian citizens. That’s crazy. Nobody thinks like that. Whether it’s in the Ukraine or Russia, people don’t think the government has the best interests of its citizens at heart. If the government found an advantage to defaulting on local debt versus foreign debt, they would certainly do that.” So here was another example of peasant logic, overlooked by the professionals.

One of the reasons to tell a story like this or to give a talk like Allen Wheat did at the conference or to write a paper is for the feedback you get. Otherwise, Wheat would never have heard from the Russian guy from Merrill Lynch nor I from the Ukrainian guy at my office. It’s good to tell stories for the feedback you get. Most of the time, the feedback is what you’d expect: “hey, funny story,” or “wow, hard to believe story.” But sometimes you get feedback you didn’t expect. So, this was one of those stories and it included a dose of peasant logic.

Joe Pimbley began his dismayingly long career as physicist, semiconductor device engineer, and applied mathematician. Thirty years ago, he diverted to Wall Street and subsequently filled numerous roles as a quantitative analyst, developer, business leader, trader, and risk manager for derivatives, structured finance, rating agencies, bond insurers, and asset managers. Joe is now a consultant and litigation expert as principal of Maxwell Consulting, LLC.

Allen Wheat resigned from Credit Suisse in 2001 after the inopportune timing of its Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette purchase, US commercial real estate losses, an IPO allocation scandal in its high-tech banking business, and run-ins with regulatory authorities in the United States, United Kingdom, Sweden, India, Japan, New Zealand, and Ukraine.

To comment on a story or offer a story of your own, email Doug.Lucas@Stories.Finance

Copyright © 2022 Joe Pimbley. All rights reserved. Used here by permission. Short excerpts may be republished if Stories.Finance is credited or linked.